Our riches did not come from piling brick on brick, or bachelor’s degree on bachelor’s degree, or bank balance on bank balance, but from piling idea on idea.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.

The commercial bourgeoisie — the middle class of traders, inventors, and managers, the entrepreneur and the merchant, the inventor of carbon-fiber materials and the contractor remodeling your bathroom, the improver of automobiles in Toyota City and the supplier of spices in New Delhi — is, on the whole, contrary to the conviction of the “clerisy” of artists and intellectuals, pretty good.

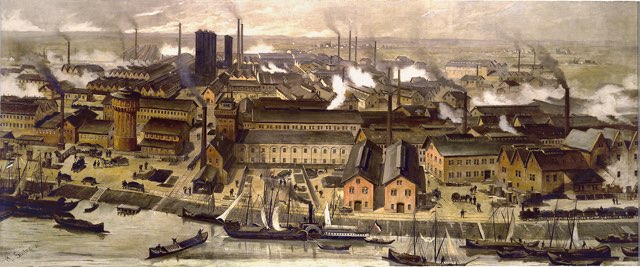

Further, the modern world was made not by material causes, such as coal or thrift or capital or exports or exploitation or imperialism or good property rights or even good science, all of which have been widespread in other cultures and other times. It was made by ideas from and about the bourgeoisie — by an explosion after 1800 in technical ideas and a few institutional concepts, backed by a massive ideological shift toward market-tested betterment, on a large scale at first peculiar to northwestern Europe.

Built on Ideas

What made us rich are the ideas backing the system — usually but misleadingly called modern “capitalism” — in place since the year of European political revolutions, 1848. We should call the system “technological and institutional betterment at a frenetic pace, tested by unforced exchange among the parties involved.” Or “fantastically successful liberalism, in the old European sense, applied to trade and politics, as it was applied also to science and music and painting and literature.” The simplest version is “trade-tested progress.” Or maybe “innovationism”?

The greatly enriched world cannot be explained in any deep way by the accumulation of capital, despite what economists from the blessed Adam Smith through Karl Marx to Thomas Piketty have believed, and as the very word “capitalism” seems to imply. The word embodies a scientific mistake.

Our riches did not come from piling brick on brick, or bachelor’s degree on bachelor’s degree, or bank balance on bank balance, but from piling idea on idea. The bricks, B.A.s, and bank balances — the “capital” accumulations — were of course necessary. But so were a labor force and liquid water and the arrow of time. Oxygen is necessary for a fire, but it does not provide an illuminating explanation of the Chicago Fire. Better: a long dry spell, the city’s wooden buildings, a strong wind from the southwest, and, if you disdain Irish immigrants, Mrs. O’Leary’s cow.

The modern world similarly cannot be explained by routine brick-piling, such as the Indian Ocean trade, English banking, canals, the British savings rate, the Atlantic slave trade, coal, natural resources, the enclosure movement, the exploitation of workers in Satanic mills, or the accumulation in European cities of capital, whether physical or human. Such materialist ways and means are too common in world history and, as explanation, too feeble in quantitative oomph.

The upshot of the new ideas has been a gigantic improvement since 1848 for the poor, such as many of your ancestors and mine, and a promise, now being fulfilled in China and India, of the same result worldwide. It is a Great Enrichment for the poorest among us. Earlier

prosperities had intermittently increased real income per head by double or even triple, 100 or 200 percent or so, only for it to fall back to the miserable $3 a day typical of humans since the caves. But the Great Enrichment increased real income per head, in the face of a rise in the number of heads, by a factor of seven — by anything from 2,500 to 5,000 percent.

The average American now earns $130 each day; in the rest of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, citizens earn from $80 to $110. The magnitude of the improvement stuns. Economists and historians have no satisfactory explanation for it. Time to rethink our materialist explanations of economies and histories.

The Betterment of Spirit

Contrary to many voices of the Left and Right, the Great Enrichment has also not come at the cost of spirit. True, shall it profit a man if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul? But the riches in our present lives allow the sacred and meaning-giving virtues of hope, faith, and transcendent love for science or baseball or medicine or God to bulk larger than the profane and practical virtues of prudence and temperance that are necessary among people living in extreme poverty. H. L. Mencken, no softie, noted in 1917 à propos Jennie Gerhardt’s and Sister Carrie’s good fortune that, “with the rise from want to security, from fear to ease, comes an awakening of the finer perceptions, a widening of the sympathies, a gradual unfolding of the delicate flower called personality, an increased capacity for loving and living.”

The bettering ideas arose in northwestern Europe from a novel liberty and dignity that was slowly extended to all commoners (though admittedly we are still working on the project), among them the bourgeoisie. The new liberty and dignity resulted in a startling revaluation by the society as a whole of the trading and betterment in which the bourgeoisie specialized.

The revaluation was derived not from some ancient superiority of the Europeans but from egalitarian accidents in their politics between Luther’s Reformation in 1517 and the American Constitution and the French Revolution in 1789. The Leveller Richard Rumbold, facing his execution in 1685, declared, “I am sure there was no man born marked of God above another; for none comes into the world with a saddle on his back, neither any booted and spurred to ride him.” Few in the crowd gathered to mock him would have agreed. A century later, many would have. By now, almost everyone.

Along with the new equality came another leveling idea, countering the rule of aristocrat or central planner: a “Bourgeois Deal.” In the first act, let a bourgeoise try out in the marketplace her proposed betterment, such as window screens or alternating-current electricity or the little black dress. With a certain irritation, she accepts as part of the deal the condition that in the second act some doubtless low-quality competitors will imitate her success, driving down the price of screens, electricity, and dresses. But if the society lets her in the first act have a go, enriching her for a while, then, by the third act, the payoff from the deal is that she will make you all rich. That’s what happened, 1848 to the present.

In other words, what mattered were two levels of ideas: the ideas for the betterments themselves (the electric motor, the airplane, the stock market), dreamed up in the heads of the new entrepreneurs drawn from the ranks of ordinary people; and the ideas in the society at large about such people and their betterments — in a word, liberalism, in all but the modern American sense. The market-tested betterment, the Great Enrichment, was itself caused by a Scottish Enlightenment version of equality, a new equality of legal rights and social dignity that made every Tom, Dick, and Harriet a potential innovator.

These are controversial claims. They are, you see, optimistic. For reasons I do not entirely understand, the clerisy after 1848 turned toward nationalism and socialism, and against liberalism. It came to delight in ever-expanding, pessimistic catechisms about the way we live now in our approximately liberal societies, whether the sin is a lack of temperance among the Victorian-era poor or an excess of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere today. One could offset the pessimism, or so the leading lights imagined, by having faith in the anti-liberal utopias of the day, which have proven immensely popular. Prohibition. Radical environmentalism. The clerisy’s pessimistic and utopian books have sold millions.

But the 20th-century experiments of nationalism and socialism, of syndicalism in factories and central planning for investment, of proliferating regulation for imagined but not factually documented imperfections in the market, did not work. And most of the pessimistic scenarios about how we live now have proven to be mistaken. Still they persist, in Senator Sanders and Mr. Trump, in Jeremy Corbyn in Britain and Marine Le Pen in France, and in less sensational form in the low opinion that people across the political spectrum hold about liberty and dignity.

No Need for Central Planning

In the 18th century, certain members of the intellectual elite, such as Voltaire and Thomas Paine, courageously advocated for liberties in trade and for the dignity that comes in the pursuit of betterment. During the 1830s and 1840s, however, a much-enlarged clerisy, mostly the sons of bourgeois fathers, began sneering at the economic liberties and social dignities their fathers were exercising so vigorously.

The conservative side of the clerisy, influenced by the Romantic movement, looked back with nostalgia to an imagined Middle Ages free from the vulgarity of trade, a non-market golden age in which rents and stasis and hierarchy prevailed. Such a vision of olden times fit well with the Right’s perch in the ruling class, governing the mere residents. Later, under the influence of science, the Right seized upon social Darwinism and eugenics to devalue the liberty and dignity of ordinary people and to elevate the nation’s mission above the mere individual, recommending, for example, colonialism and compulsory sterilization and the cleansing power of war.

On the left, meanwhile, the radical intellectuals and elites — also influenced by Romanticism and then by their own scientistic materialism — developed the illiberal idea that ideas do not matter. What matters to progress, the Left declared, is the unstoppable tide of history, aided (it declared further, contradicting the supposed unstoppability) by editorials or protests or strikes or revolutions directed at the ravenous bourgeoisie — such thrilling actions to be led, of course, by the intellectuals themselves.

Later, in European socialism and American Progressivism, the Left proposed to defeat bourgeois monopolies in meat and sugar and steel by gathering under regulation or syndicalism or central planning or collectivization all the monopolies, merging them into one supreme monopoly called the State. In 1965, the Italian liberal Bruno Leoni (1913–1967) observed that “the creation of gigantic and generalized monopolies is [said by the Left to be] precisely a type of ‘remedy’ against so-called private ‘monopolies.’”

While all this deep thinking was roiling the clerisy of Europe, the commercial bourgeoisie — despised by the Right and the Left, and by many in the middle, too, all of them thrilled by the romance of works such as Mein Kampf and Lenin’s “What Is to Be Done?” — created the Great Enrichment and the modern world, proving that both social Darwinism and economic Marxism were mistaken.

The genetically inferior races and classes and ethnicities and genders proved not to be so. They proved to be creative. The exploited proletariat was not immiserated. It was enriched.

In its enthusiasm for the materialist but deeply erroneous pseudo-discoveries of the 19th century — nationalism, socialism, Benthamite

utilitarianism, hopeless Malthusianism, Comtean positivism, neo-positivism, legal positivism, elitist Romanticism, inverted Hegelianism, Freudianism, phrenology, homophobia, historical materialism, hopeful Communism, leftist anarchism, communitarianism, social Darwinism, “scientific” racism, racial history, theorized imperialism, apartheid, eugenics, tests of statistical significance, geographic determinism, gender determinism, institutionalism, intelligence quotients, social engineering, slum clearance, Progressive regulation, cameralist civil service, the rule of experts, and a cynicism about the force of ethical ideas — the clerisy mislaid its earlier commitment to a free and dignified common people. It forgot the main, and the one proven, social discovery of the 19th century: Ordinary men and women do not need to be nudged or planned from above, and when honored and left alone become immensely creative. “I contain multitudes,” sang the democratic, American poet. He did.

The Great Enrichment, in short, came out of a novel, pro-bourgeois, and anti-statist rhetoric that enriched the world. It is, as Adam Smith said, “allowing every man [and woman, dear] to pursue his own interest his own way, upon the liberal plan of equality, liberty, and justice.”

Reprinted from National Review