Mr. Lawrence Reed of the Foundation for Economic Education has just written this timely commentary.

Mr. Lawrence Reed of the Foundation for Economic Education has just written this timely commentary.

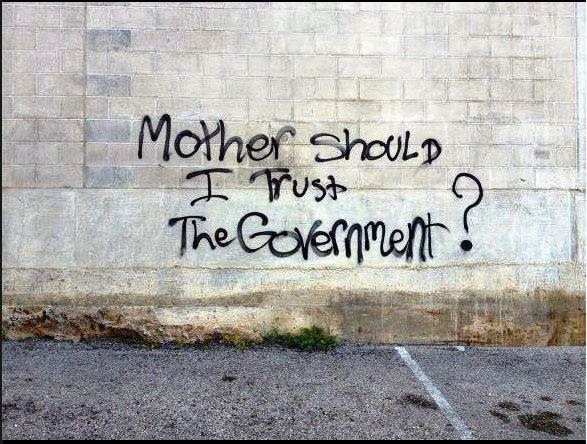

With so much talk these days of scandal, incompetence, and failed programs, trust in government is on the ropes. To some people, this development is lamentable. They are busy writing columns and editorials about the need to “renew our faith in democratic institutions.”

But among those who understand the difference between government in the abstract and government in reality—between what America’s Founders had in mind and how today’s politicians actually behave—declining trust in government evokes a contrasting view: it’s richly deserved, long overdue, and we should pray for more of it.

Recent polls testify to a fading faith in government. A CBS News/New York Times poll earlier this month found that 70 percent of Americans are dissatisfied or angry with the way elected officials in Washington handle the business of the people. A remarkable 80 percent said that members of Congress are more interested in pandering to special interest groups than in serving the needs of people who elected them. A mere 13 percent believe that Congress represents the interests of the people at large.

Furthermore, the CBS/New York Times poll concluded that “Fifty-nine percent of Americans think the government is doing too many things better left to businesses and individuals, a percentage that has been consistent for many years. Fifty-six percent would choose a smaller government providing fewer services over a bigger government providing more services, up from 48 percent last spring and the highest percentage in more than a decade.”

Late last summer, a Gallup poll asked Americans this question: “How much of the time do you think you can trust government in Washington to do what is right—just about always or most of the time vs. only some of the time or never at all?” Only 19% responded “just about always or most of the time”—which I suspect may roughly correspond to the number of people at any given moment who are lying, stoned, drunk, deaf, out of their minds, or comatose. Eighty-one percent answered correctly—“only some of the time or never.”

To put it bluntly, it’s just plain stupid to lament a decline in trust in government until you find out why it’s happened. Context is critical here. When the British monarchy was perpetrating “a long train of abuses and usurpations,” sending forth “swarms of officers to harass our people and eat out their substance,” it was hardly a lamentable fact that American citizens lost faith in King George. They would have had to be generally insensate NOT to lose faith.

America’s Founders did not want a government in which the citizens placed blind confidence. Thomas Jefferson was especially noted for his desire to cultivate a healthy distrust of the state. To Abigail Adams in 1787 he wrote, “The spirit of resistance to government is so valuable on certain occasions, that I wish it to be always kept alive. . . . I like a little rebellion now and then. It is like a storm in the atmosphere.”

The steep decline in trust in government since the mid-1960s is proof that large numbers of Americans are awake and learning something. Politicians who promised the sky delivered the proverbial mess of pottage instead. Remember the assurances of how billions of tax dollars siphoned through the federal bureaucracy would solve poverty? The result would be laughable were it not so tragic, so obviously tragic that a president of the same party as Franklin Roosevelt signed a bill in 1996 to end the federal entitlement to public welfare.

If, after the experience of the last 40 years, Americans had lost no faith in government welfare programs, they would likely be diagnosed as possessing a prime symptom of clinical insanity: doing the same harmful thing over and over again and expecting different results each time.

Few if any polls or surveys separate out what people think of the basic, original framework of American government from what they think of the characters who are actually doing the governing. I suspect that if you asked a cross section of citizens, “Do you trust the concepts embraced by the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States?” you’d get a higher number than if you asked, “Did you trust Richard Nixon after Watergate?” or “Did you trust John Edwards when he said he was faithful to Elizabeth?”

What’s lamentable here is that more than a few of our politicians lie, cheat, and steal. It is not lamentable that Americans lose faith in them when they do those things. It is laudable, because it is common sense being appropriately applied.

After all, what does it mean to “trust” someone or something? It means the object of that trust has earned respect and confidence through high standards of reliability, truthfulness, and performance. I can think of no reason why governments deserve your trust any more than anything or anyone else when they fail to meet those standards.

In fact, I can think of a reason why government ought to be held to even higher standards: unlike private individuals or private institutions, it has the legal power to seize your assets whether you trust it or not. If the French political philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was right (and on this score, I think he was), then it isn’t too much for citizens to ask their government to at least be honest with them: “To be governed is to be watched over, inspected, spied on, directed, legislated at, regulated, docketed, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, assessed, weighed, censored, and ordered about, by men who have neither the right nor the knowledge nor the virtue.”

If Americans had really lost all faith in the state, however, they would want to take back the responsibility for their retirement years and get rid of the Ponzi scheme albatross known as Social Security. They would assume the duty of making sure their children are educated and yank them out of union-run government schools. I haven’t seen any polls yet that would suggest a majority of Americans are ready for such rugged individualism. So in some respects we could benefit from even further erosion of “trust in government.”