Academics, politicians, clerics and others always seem perplexed by the question; why is there poverty? Answers usually range from allegations of exploitation and selfishness to slavery and colonialism and other forms of less than moral behavior.

Academics, politicians, clerics and others always seem perplexed by the question; why is there poverty? Answers usually range from allegations of exploitation and selfishness to slavery and colonialism and other forms of less than moral behavior.

Poverty is seen as something to be explained with complicated analysis conspiracy doctrines and incantations. This vision of poverty is part of the problem in coming to grips with it.

There is very little that is complicated or interesting about poverty. Poverty is man’s global condition throughout his history. The causes for poverty are quite simple and straight forward. Generally people are poor for one or more of the following reasons; (1) they cannot produce many things highly valued by others, or (2) they can produce things valued by others but they are prevented or (3) they volunteer to be poor.

The truly mysterious question is; how come there is affluence? That is, how a tiny proportion of man’s population (mostly in the West), for only a tiny part of man’s history (mainly in the 19th and 20th centuries), manage to escape the fate that befell his fellow man? In a word, how did western people become so productive?

Sometimes people try to answer this question, in reference to the United States, by pointing to its rich endowment of natural resources. The natural resources explanation of affluence fails to provide a satisfactory explanation. Were abundant natural resources the cause of affluence, Africa and South America would stand out as the richest continents. Instead, these two continents are home to some of the poorest people on the face of the earth. By contrast, the natural resources argument would suggest that natural resources scarce countries like Japan, Hong Kong and Great Britain would be poor instead of ranking among the richest countries.

Another unsatisfactory explanation of poverty is the colonialism argument. This argument suggests that Third World poverty is a legacy of history of having been colonies. But it turns out that countries like the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand were colonies; yet they are among the world’s richest countries. On the other hand Ethiopia, Liberia, Tibet and Nepal were never colonies and they rank among the world’s poorest and most backward countries.

Despite the many justified criticisms of colonialism and, I might add multinationals, the fact of the matter is that both served as a means of transferring of the technology and institutions bringing backward peoples into greater contact with a more developed western world. The fact of the matter is most countries of Africa have suffered significant economic decline since independence i.e. after the colonists departed. In many of those countries the average citizen can boast that he ate more regularly and had greater human rights protections under colonial rule. The colonial powers never perpetrated the human rights abuses that we have seen in the post-independent Burundi, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Central African Empire, Somalia and elsewhere.

Any economist who suggests he has a complete answer to the causes of affluence should be viewed with suspicion. We do not know exactly what makes some societies more affluent than others. However we have hunches based on correlations. Affluence, it would appear, is related to several factors of the human condition found in society. Let us try a somewhat crude first approximation. Start out by ranking countries according to their economic systems. Conceptually we could arrange them from those more capitalistic (having a larger free market sector) to the more communistic (with extensive state intervention and planning). Then consult International Amnesty’s ranking of countries according to human rights protections to those with the least. Then finally use United Nations statistics and rank countries from highest to lowest per capita income.

Having compiled the three lists, one would observe a very strong though imperfect correlation: those countries with market forces playing a great role tend also to have stronger protections of human rights. And as an important side benefit of greater economic liberty their people are wealthier. Such a finding isn’t a coincidence so let us speculate on the relationship.

One way of defining human rights protection is to ask to what extent does the state honor and protect peaceable, voluntary exchange and private property rights. Let me clarify a bit. Most people share my value that people should own themselves. However in order to own oneself has little meaning. In fact, a good working definition of slavery is a set of conditions where you do not own anything of what you produce; your entire productive output belongs to someone else and it is he who determines its disposition. And, by the way, there is no distinction, as often alleged, between property rights and human rights; they are one and the same.

Private property rights are those rights held by the owner to keep, acquire and dispose of property in any fashion so long as he does not violate the private property rights of others. Private property rights versus collectively held rights are not simply a matter of philosophical differences. Private property rights systems produce incentives and results that systemically differ from those found with collectively held rights.

Since collectivists often trivialize private property rights, it is worthwhile to spend a few minutes elaborating a bit. When property rights are held privately, the costs and benefits from individual decisions are concentrated while with collectively held rights to property the costs and benefits of individual decisions are dispersed.

Consider the person who privately owns his home. It is in his financial interests to voluntarily care for the house and make those sacrifices of current consumption, such as buying fewer luxuries in order to maintain his house in good repair. In other words, private property forces people to take into account the effect of their current decisions on the future of property. That is, the value of his house depends on the length of time the house will provide housing services. The longer it can, the higher the selling price it will fetch. Thus privately owned property holds one’s personal wealth hostage to doing the socially responsible thing – economizing on society’s scare resources.

Contrast these incentives to those where there is collective ownership i.e., the government owns the house. There is reduced incentive to take care of the house simply because the individual does not capture the full benefit of his efforts. In contrast to private ownership the benefits of his actions are dispersed across society as opposed to being concentrated. The costs of not caring for his house are not fully borne by him; they are dispersed across the entire society. Thus he captures a smaller benefit from his socially responsible behavior and bears a smaller cost of his socially irresponsible behavior. You do not have to be a rocket scientist to predict that when the benefits of an action (caring for property) are reduced, less of that action is seen when the costs of an action (not caring for property) are reduced, more of that action is seen. Therefore, we may conclude that whatever strengthens private property will get people to voluntarily conserve scarce resources and whatever weakens private property will tend to get people to waste scare resources.

This scenario would be incomplete if it left one with the impression that nominal collective ownership was the only weakening force for social responsibility. Taxes represent government claims to private property. When government taxes property, it changes it ownership characteristics. Therefore, if government were to impose a 75 percent tax when a person went to sell his house, it would have effects similar to government ownership i.e. reducing individual incentives to wisely use the house.

While I have used the example of home ownership to make my argument concrete, the phenomena is general and applies to all activities including work and investment. Whatever interferes with a return from, or raises the cost of, and investment reduces incentives to make that investment in the first place. This applies to investment in human as well as physical capital.

We can think of investment in human capital as those activities that raise the productive capacity of individuals. Among these activities are health, education, on-the-job-training and migration. Whatever raises the cost of engaging in these productivity raising activities will discourage them and whatever raises the net benefit to the individual will encourage them. Not being that familiar with the institutional structure of this country, I will simply list general factors that influence benefits and costs of human capital.

Factors that raise costs of human capital acquisition are: restrictions on people’s ability to receive on-the-job training to raise their skills such as restrictive licensing laws, minimum wage, equal-pay-for-equal-work laws and restrictive union employment practices. Regardless of any other stated intention behind these laws, their effect is to preclude entry and skills upgrading by individuals who do not meet a certain skills level. That is, these entry restrictions have the full effect lf a law that says, “If you have not achieved a certain level of productivity, you are not deserving of a job and a chance to raise that productivity through work-associated training.”

Human capital investment is also hampered by “imperfections” in markets for borrowing. Typically, a person borrowing for Investment in physical capital can offer the lender collateral. The effect of being able to offer collateral reduces the risk seen by the lender. In investment in human capital, individuals cannot typically offer the lender collateral against default.

Factors that lower the benefit to investing in human capital are high marginal tax rates, uncertainty about return and weak property rights. That is, as discussed in the house ownership scenario, anything that reduces the individual’s ability to capture the returns to him productive activity reduces his incentive to invest. Work effort and investment are highly related to property rights. In other words, if we tax something we can expect to get less of it. By taxing work and investment effort, we in fact lower the cost of engaging in leisure activity (not working). This effect is enhanced and reinforced by welfare programs.

To a significant degree, the wealth of nations is embodied in its people. This can readily be seen by the experience of the German people after World War II. During the war, Allied bombing missions destroyed nearly the entire stock of German physical capital. What was not destroyed was the human capital of its peoples held in the form of skills and education. In the relatively short space of two decades, West Germany reemerged as a formidable economic force. The Marshall Plan, as it is often alleged, and other US subsidies to Europe cannot begin to explain its recovery after World War II.

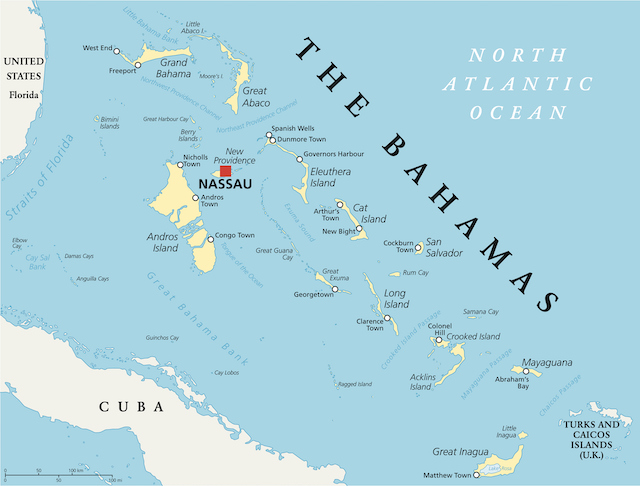

While Bahamian per capital income is considerably higher than other West Indian countries, we see a very interesting pattern when they and other West Indians move to the United States. When people manage to escape their government controls and come to the relatively freer markets of the United States, by the second generation, they manage to earn median family incomes slightly higher than the average American white. Moreover, they are more highly represented in the professions than either American blacks or whites.

Therein lies much of the tragedy of many countries. Their people do fairly well when they leave their country but not in their country, in a large part due to the stifling regulatory atmosphere. But West Indians are not alone in this respect. Mainland Chinese all of a sudden move up the economic ladder when they migrate to Hong Kong. Vietnam and Cambodian refugees become wealthier when they migrate to the US and Canada. Indians become more successful when they leave India and come to England, the US and Canada.

Proper identification of the causes of poverty is critical. If poverty is seen, as is too often the case, as a result of exploitation, the policy recommendation that naturally emerges is one of income redistribution i.e., government confiscation of some people’s “ill-gotten” gain and restoring them to their “rightful” owners. This is the politics of envy and begging where domestically people call for bigger and bigger welfare programs and internationally they call for bigger and bigger foreign aid programs. If poverty is correctly seen as a result of the lack of productive capacity and government intervention, other policy recommendations follow.

An important component of Bahamian policy for greater wealth should be obvious from this discussion. Public policy should be that of non-interference, promotion of private property rights and the provision of high quality education. Given economic freedom, I am sure Bahamians can make economic growth a prosperous hobby.

Speech by Walter Williams PhD, delivered at a Bahamas Chamber of Commerce Dinner, April 28th 1994.

The views expressed are those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Nassau Institute (which has no corporate view), or its Advisers or Directors.